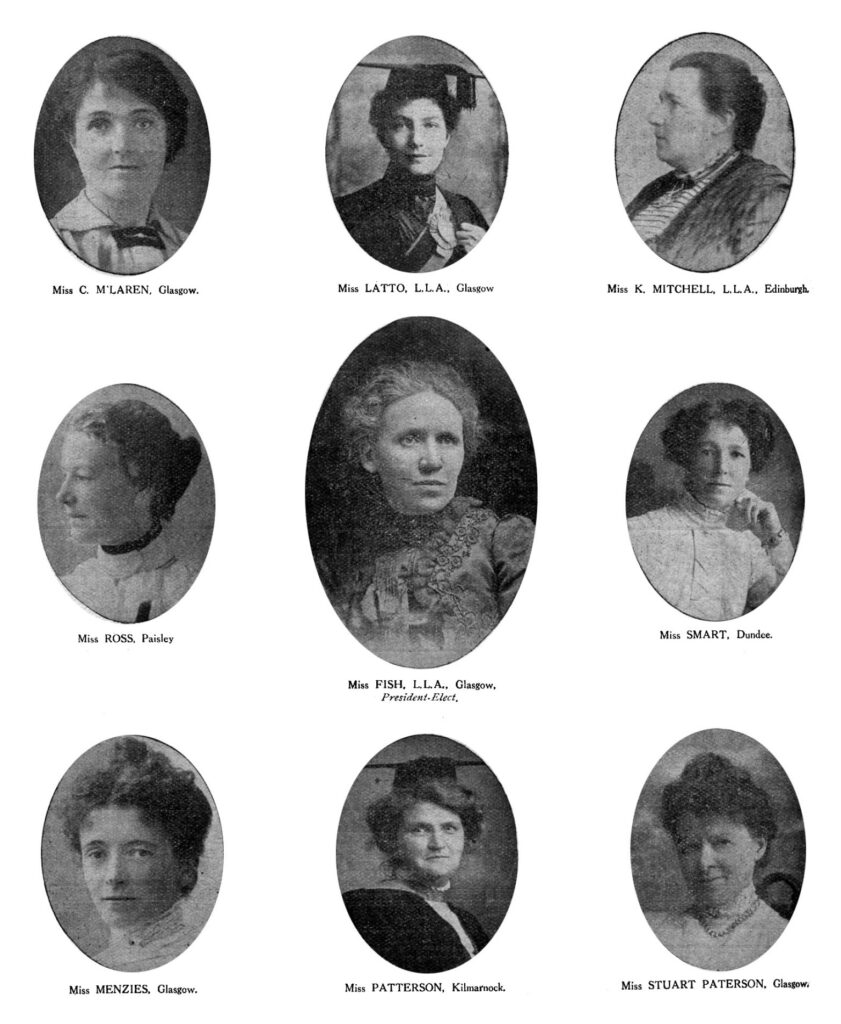

It is now a matter of common knowledge that Miss Elizabeth Fish, L.L.A., F.E.I.S., has been by a very large majority selected from four candidates for sole nomination to the annual general meeting in September as president of the Educational Institute of Scotland for the year 1913-1914.

As the annual general meeting has, under the rules and regulations, the ultimate say, irrespective of the voting which takes place annually, as to those who shall fill the presidentship and the vice-presidentship, and those who shall act on the council, we have carefully abstained from using in the present instance that otherwise useful word “elected” – although everyone knows that for all intents and purposes, the “election” which has just been completed settles the whole matter.

We therefore take it that Miss Fish is at this present moment as much and as really president for the next Institute year as she will be when she shall have been formally installed in office in September. Whatever the future may bring forth, it is therefore an indubitable fact that for the first time in the history of the Educational Institute since its foundation in 1847 a woman teacher is the recipient of the highest honour which can be conferred by teachers upon a teacher.

It may at first sight, in view of much that has happened in the past, be a matter to occasion surprise that such a thing should occur; to us it is a matter of surprise that it has not happened long ago. Consider the changed and ever-changing conditions under which the teaching profession stands in 1913 compared with those obtaining when the Institute was founded, for the first 25 years after its foundation, and for the remanent period of 40 years which completes the whole period under review.

When the Institute was founded in 1847, education was looked upon as a man’s work, not a woman’s. In making this broad statement we do no injustice to the “Ailies”, about whom distinguished authors write, and about whom Miss Fish lectures so acceptably, who, through the dual gateway of the “Carritch” and the Holy Bible, led their very youthful flock along the earlier stages of the paths of learning.

It is not wrong to say that prior to the passing of the great Education Act of 1872, women teachers were practically unknown in Scottish schools. But a change began in 1873, a change which is still in process, the end of which no-one can foresee. Few in number during the “seventies”, and comparatively few in the “eighties”, women have come into their own during the last 20 years to such a degree that in our schools they now outnumber the men by six to one. But in this development Scotland lags notoriously behind America, where, as regards both Canada and the United States, the schools are almost exclusively “manned” by women.

As we are convinced that school best fulfils its complex purposes which is most nearly a replica of the home, room for both the paternal and the maternal elements, and it will not be a good day for Scotland which finds men banished from the work of both primary and secondary education. Granting proper and reasonable inducements, such a break from the great traditions of the past need never be.

Nor is there room for the suggestion that there is a necessary element of antagonism in the matter. As Miss Fish has wisely said, there is no profession other than teaching in which men and women work side by side so harmoniously and with a view to the common good as in the teaching profession.

Long may this wholly satisfactory relationship continue. In the school and in the profession, men’s problems are women’s problems; neither group can be solved separately, both may reach solution through, as hitherto, concurrent action. For example, the shameful salaries paid to so many women teachers in rural and in some provincial town schools will not be raised to a fairly reasonable amount without the help of men teachers and of that great organisation which was founded by men and up to the present time has so largely been guided by men.

At the same time very valuable work has in recent years been done by the women members of the council – a band relatively few in numbers but strong in influence. This influence cannot but be enhanced by the advent of a woman president. We predict Miss Fish and for the Institute a useful and successful year’s work, and we are confident that not only the members of council but every member of the Institute will rally to support the first woman occupant of the presidential Chair.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Research, interviews and substantive writing:

Adi Bloom

Design and lay-out:

Stuart Cunningham and Paul Benzie

Additional writing and research:

EIS Comms Team and assorted staff members

Printed by:

Ivanhoe Caledonian, Seafield Edinburgh

Photography:

Graham Edwards, Mark Jackson, Elaine Livingston, Toby Long, Ian Marshall, Alan McCredie, Alan Richardson, Graham Riddell, Lenny Smith, Johnstone Syer, Alan Wylie

Thanks to the many former activists and officers who gave of their time to be interviewed and taken a stroll down memory lane. And of course a very special thanks to the EIS members who created this history through their activism and commitment to the cause of Scottish Education.

© 2022 The Educational Institute of Scotland