The blurb to David Ross’s An Unlikely Anger – Scottish Teachers in Action states: “From 1984 to 1986 Scottish teachers were involved in the most sustained campaign of industrial action in the history of Scottish education – a dispute which had implications for the trade-union movement in Thatcher’s Britain. An Unlikely Anger tells the story of how Scotland’s teachers became the first public-sector group to make the government turn when it was not for turning.”

The recommencement, following Clegg, of a cycle of decline saw the EIS enter into a significant pay dispute that fundamentally changed the character of the union, defining it for a new era. The teacher-strike campaign across 1984-1986 was critically important to the development of the EIS. There was a growing awareness of the fact that teachers had to fight to get things, and a strong commitment and belief that collective action would get them. Many argue that it was the sustained action of the 1980s that completed the EIS’s transition into a trade union

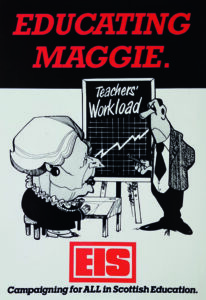

Against the backdrop of Margaret Thatcher’s government and its bitter dispute with the miners, the mid-1980s teachers’ strikes were deliberately planned to ensure sustainable action with maximum impact. Firstly, it was a targeted action: strikes were specifically focused on the constituencies of Cabinet ministers, for example. Secondly, they were rolling strikes, so that individual teachers might be out of school for only one day of the week – losing only one day’s pay – but the overall effect was that the school was unable to operate.

EIS members also contributed to a national levy to subsidise members in those schools where repeated action was being taken.

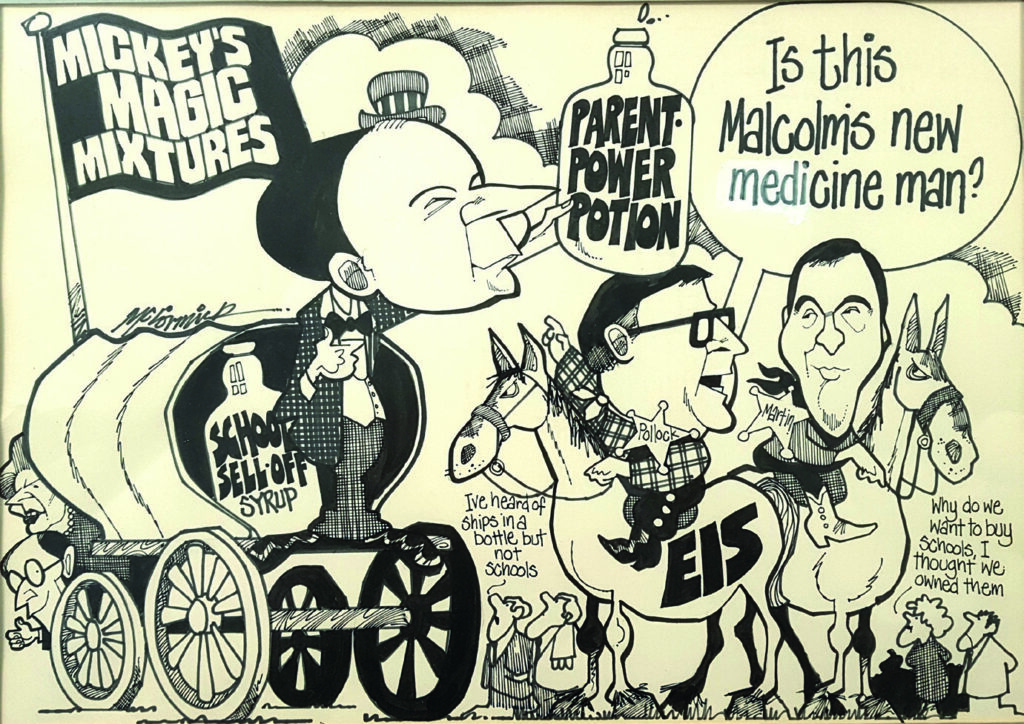

Key among the EIS leaders was John Pollock, who had been EIS general secretary since 1975, and to whom the success of the 1980s strikes is widely attributed. Ronnie Smith, who served as general secretary from 1995 to 2012, refers to Pollock as “the architect of the modern EIS,” and “one of the few people whose eloquence actually made a difference to the outcome of the negotiations.”

For the first time, the EIS began to appeal to a vast range of teachers, activist and otherwise. Hundreds of people who had never previously been involved in union politics began turning up to EIS meetings. And striking teachers from across Scotland – some from as far afield as Dumfries or the Orkneys – crowded into George Square in Glasgow for a massive rally.

There was a determination that the union had to succeed, for the greater good of the teaching profession.

The EIS was sensitive to making sure it kept parents and the broader public on side. But public support was never really in doubt: attempts to whip up any kind of crude anti-teacher sentiment never really took off. Scotland, never particularly fond of the Tories, understood that the action was a blow against Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government, and it welcomed that.

The result of the teachers’ strike action was a government review by Sir Peter Main. This recommended a major pay award, as well as some adjustments to teachers’ working conditions. It was widely regarded as a significant win for the EIS and a defeat for the government.

The agreement also created a common pay scale for primary and secondary teachers, so that primary teachers could achieve the same top salary as secondary teachers – a major change

llustrations by Malky McCormick

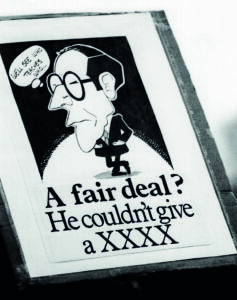

A play on the popular Castlemaine XXXX adverts of the time

Perhaps as important as the immediate outcome was the changed nature of the Institute. Having successfully pursued industrial action against an intransigent UK government, there was little inhibition about the use of the same tactic in other areas – the 1980s, for example, also saw widespread action to secure three-day cover with members refusing to cover classes for absent colleagues for any longer than three days, insisting that supply staff were brought in for that purpose.

During the action, such a refusal led to teachers being “deemed” (i.e. deemed to have breached their contracts and therefore not entitled to payment).

However, this just raised the level of disruption, as “deemed” teachers simply refused to teach any classes, and on union advice retired to the staffroom.

Eventually council after council agreed a three-day cover policy, limiting the workload imposition on permanent staff and opening up employment opportunities for others.

Larry Flanagan, the current general secretary, began teaching in 1979 and experienced the 1980s campaign as his first introduction to the EIS. “Looking back, it’s interesting to note how many young activists from that period went on to become EIS presidents, officers and officials, and even general secretary.

The campaign certainly instilled in me a belief that teachers would take on a fight when required to do so and I think our subsequent campaigns, not least the Value Education Value Teachers pay campaign, is testimony to that.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Research, interviews and substantive writing:

Adi Bloom

Design and lay-out:

Stuart Cunningham and Paul Benzie

Additional writing and research:

EIS Comms Team and assorted staff members

Printed by:

Ivanhoe Caledonian, Seafield Edinburgh

Photography:

Graham Edwards, Mark Jackson, Elaine Livingston, Toby Long, Ian Marshall, Alan McCredie, Alan Richardson, Graham Riddell, Lenny Smith, Johnstone Syer, Alan Wylie

Thanks to the many former activists and officers who gave of their time to be interviewed and taken a stroll down memory lane. And of course a very special thanks to the EIS members who created this history through their activism and commitment to the cause of Scottish Education.

© 2022 The Educational Institute of Scotland